Wadzanai Motsi

Thomas J. Watson Fellow 2013Project

Speaking Up: Unearthing the Motivation for Youth Political Activism

Egypt, Tunisia, Ghana, The Czech Republic, Cambodia

Follow Wadzanai's journey

I came to Grinnell College as an international student from Zimbabwe, so when I applied for the Watson, I was already living abroad. But the Watson challenged me to explore the whole world. I wanted to know what motivates young people to participate in national politics around the globe, especially in places where the government had failed them. My Watson journey taught me a great deal about that, but it also led me to experiences I couldn't have imagined or prepared for. It was profound, intense—the definition of self discovery.

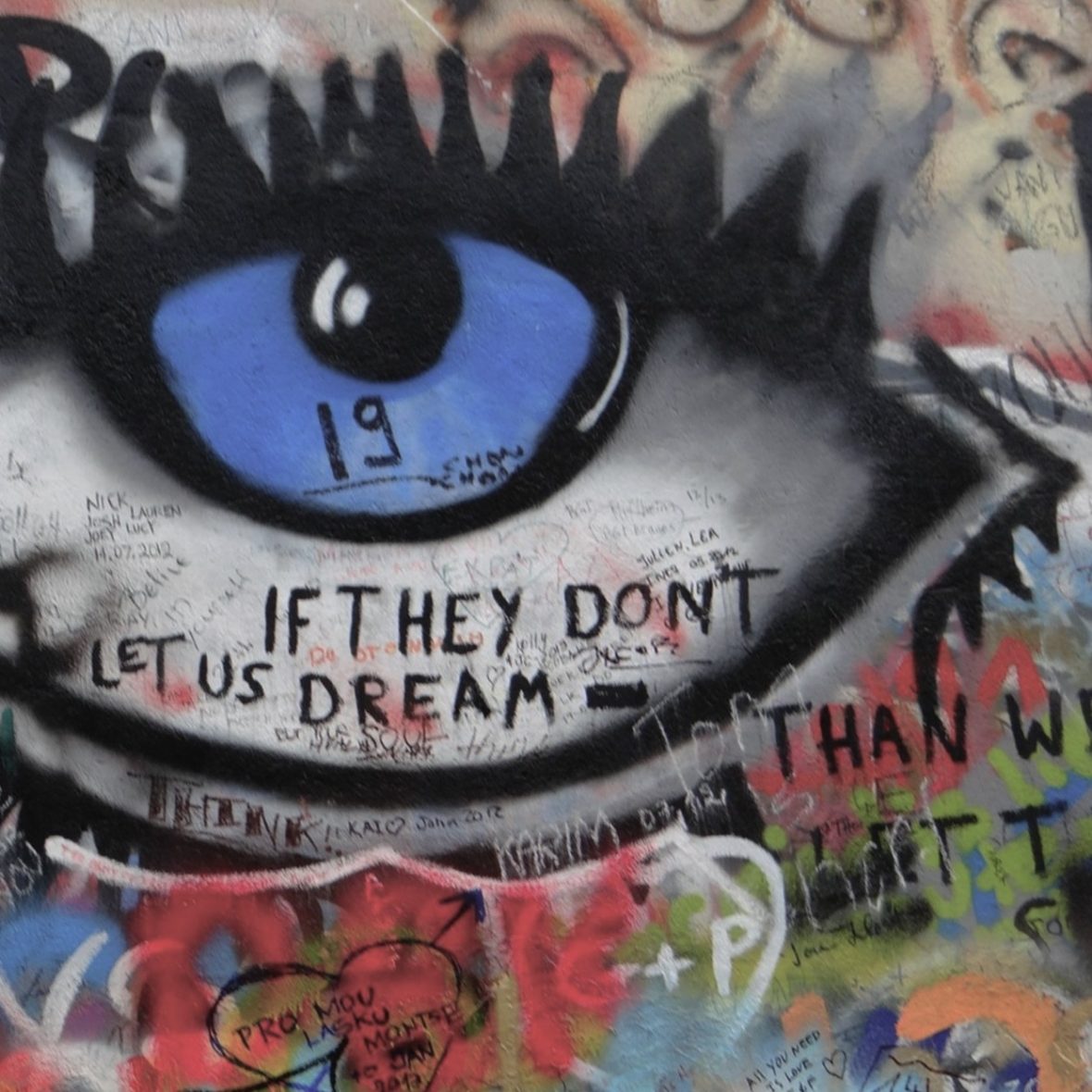

I arrived in Egypt expecting the energy and chaos I’d seen in news reports of the revolution in Tahrir square, but I found a country engaged in a moment of reflection. Events had unfolded so fast that people seemed to be using the tranquility of Ramadan to process all that had happened, and I had many quiet conversations with ordinary Egyptians who were deeply uncertain about what the revolution had meant. One young man, trained as an engineer, had found his calling during the revolution as a graffiti artist; the revolution had showed him the possibility of a different kind of life for himself and his friends. Other activists were more discouraged. I spoke with a woman who was surprised at the liberals’ loss in the presidential election, and she blamed herself. “We didn’t share what we believed in with the rest of the country,” she said, “so they didn’t understand us.”

Egypt

Another woman, in a town on the shores of the Red Sea, told me that she didn’t know what the Cairo protestors had been trying to achieve. She’d seen only negative effects from the revolution as her town’s economic lifeblood, tourism, had dried up. This diversity of opinion surprised me, but it set the tone for a year that was more reflective—and at times, sobering—than I first thought it would be.

Tunisia

During the Ghanaian presidential election, I volunteered with the Institute for Democratic Governance (IDEG), a think tank based in Accra which promotes transparency and fairness in electoral politics. I helped IDEG create a report on the election by following the news, visiting polling stations, and doing administrative tasks, from taking photographs to compiling reports. It felt good to be part of a team, and I was impressed by IDEG’s message of peace, especially since violence had tainted many recent African elections. But I also felt that the Ghanaian political system often used young people as foot soldiers for entrenched interests, rather than looking to them for inspiration. The young people I met and worked with were surprisingly frank. They understood that their role as youths was to organize for their leaders; in time they would be the leaders and able to make decisions themselves.

Ghana

As the year progressed, I had to confront questions about myself and my project that I hadn’t expected to face. I’d set out looking for politically minded young people who cared about a world bigger than themselves and were altruistic in their intentions—people, I thought, like myself. But I came to feel that in the ‘real’ world, altruism does't exist without self-interest, and this was something of a shock. How could I help people feel empathy toward disenfranchised, poorer, and violated members of our societies if that empathy wasn’t innate? I remembered my conversations with an activist in Egypt. She told me that when you are convinced of your struggle you assume everybody understands what that struggle is, but in reality you have to communicate it, and ask people if they agree. You can’t take them for granted.

Ultimately I came to feel that only experience can shape compassion; and experience, for young people, is often in short supply. But hope and the willingness to learn are not. I often think about a young man I met in the Czech Republic. After he spent several days with the Roma community as part of a college class, his sense of poverty as a distant phenomenon changed. He personalized their struggles because he was among them, and they were so close to what he called home. I found myself re-examining the experiences that led me to my own views about the world, and I wondered how my future self might be able to provide these kinds of experiences for others.

The Czech Republic

By the time the national election campaign picked up in Phnom Penh, the streets were jammed with chanting motorcyclists. Blue and yellow party flags waved and voters held up their fingers touting their party's number on the ballot. This July election was special: Cambodia's two main opposition parties had joined forces, presenting voters with an alternative to the party that had ruled for decades. Many young people clearly hoped their voices would be heard for the first time, and I couldn’t help contrasting the scene in Cambodia with the election at home in Zimbabwe. I was glad to see their enthusiasm; I also knew that some disappointments probably awaited them. But my Watson year taught me that when you realize the world is bound to fall short of your hopes, you also see the world more clearly—which is a first step toward making real change. I still believe we can build a better world, but I have a firmer grasp of the enormity of the challenges.

Cambodia

Where they are today

Co-Founder at Sangano Black Business Hub | Berlin, Germany

Our Programs

Our Fellows

Through two, one-of-a-kind programs we encourage students to create personal pathways, then support their journeys.