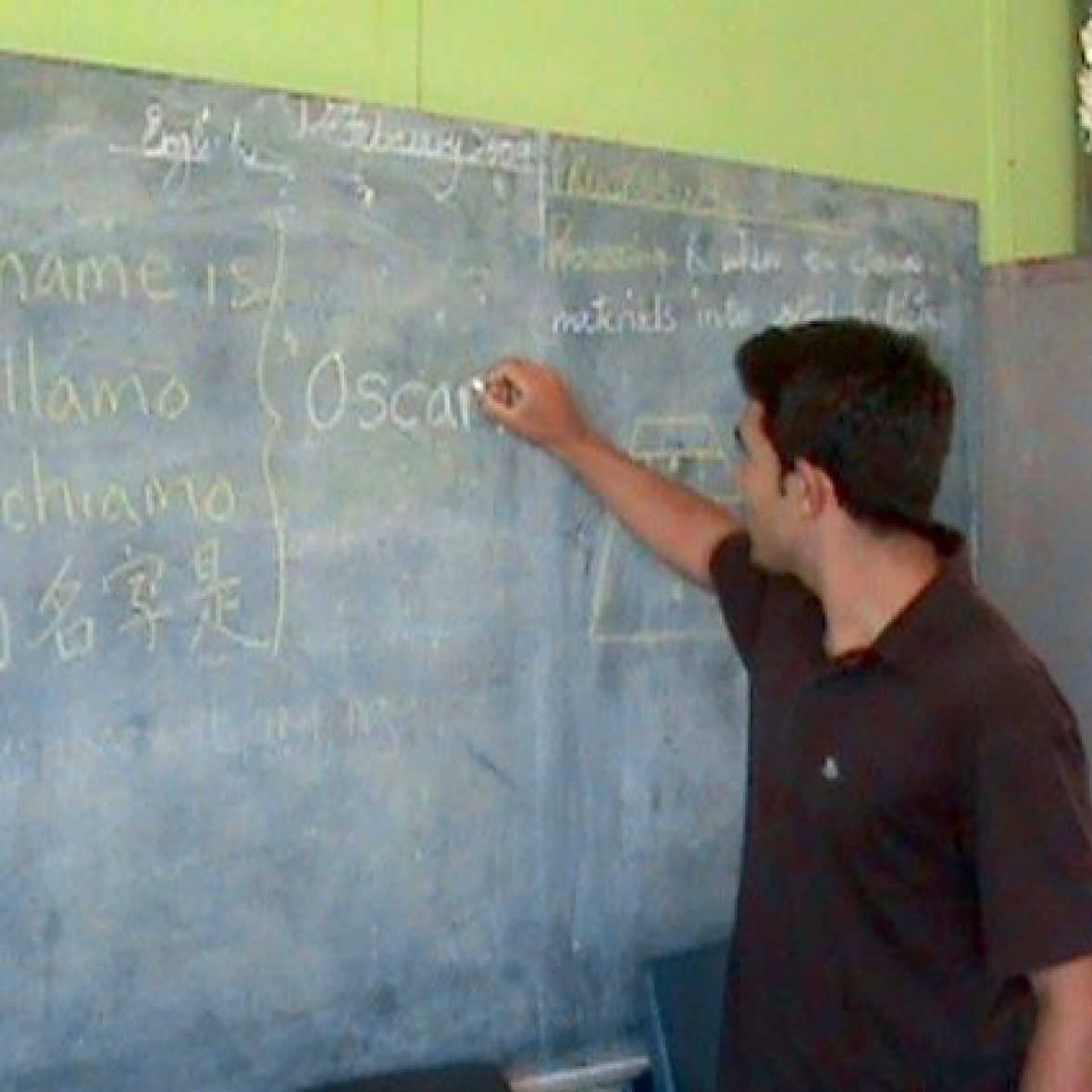

Oscar Baez

Thomas J. Watson Fellow 2008Project

Language Activism: Safeguarding Linguistic Heritage in Multilingual Societies

Mexico, Brazil, South Africa, Turkey, Spain, Singapore, Malaysia

Follow Oscar's journey

I grew up in a household of immigrants. My parents moved to the USA from the Dominican Republic when I was three, and I can’t remember a time when I didn’t speak both English and Spanish. But my parents never really learned to speak English, and it was a barrier that kept them from pursuing their dreams. Growing up, I had to serve as their translator, which planted the seeds of my passion for languages that grew into studies of Mandarin and Italian—and bloomed in my Watson year.

My journey began in Mexico, where I attended a Forum on Language Planning at the Intercultural University of Chiapas—the first indigenous university in Mexico—where representatives of the different dialect groups of the Mayan language had gathered to create a written form of Mayan on which they could all agree. It was incredible to be present at the creation of a written language, and I was mostly a fly on the wall, but I tentatively joined in some breakout discussions, where we talked about everything from poetry to the use of the Tzotzil dialect in television and film, and a few attendees even asked if I was a linguist. I couldn’t believe I had this kind of access. As a foreigner and the only Spanish-speaker with a Dominican accent, I never thought I would fit in so well, yet there I was, comfortable in this new skin. For the first time, I thought: I could do this. I could be this.

Intercultural University of Chiapas

Mexico

Arriving in Brazil, I was instantly immersed in the Portuguese language, and my progress ground to a halt. I had thought that my native Spanish would make Portuguese fairly easy to master, but it turned out to be a roadblock that took a long, exhausting month to overcome. I often felt isolated and homesick, and I hit a low point when the bag containing my computer (and my video recordings of the Mexican conference) was stolen out from under me at a café. But I slowly began to feel the courage to extend myself, to make connections, to start conversations without the fear that I’d be tongue-tied. I visited the unique Museum of the Portuguese Language in Sao Paulo, lived with a local resident in Ipanema, and spent Christmas with strangers-turned-friends in the city of Bahia (after a three-day-long bus journey together up the Atlantic coast). By New Year’s Day, I was dreaming in Portuguese.

Brazil

It was strange to watch Barack Obama’s second inauguration from South Africa, but it also felt appropriate; there, as in the United States, the shadow of race looms over the country’s politics and languages. On paper, South Africa’s constitution lists eleven official languages, but in practice the languages of white South Africans—English and Afrikaans—still dominate, in part because of pressures to speak languages associated with employment and opportunity. As the director of the Center for Research on the Politics of Language explained to me, no matter how well-intended a language policy may be, unless the speakers of a minority language promote the use of their tongue at home, it will fall by the wayside. Still, I was astonished at how multilingual South African society was; even white South Africans often conversed in three or four languages in the course of daily life, and this wasn’t considered unusual. That fact, more than any other, gave me hope for their future and the resilience of a polyglot world.

South Africa

When I landed in Turkey, I realized that I had saved the most difficult parts of the year for last, which in hindsight might not have been the best decision as my stamina was wearing down. Everywhere I’d been in the last eight months, even French-speaking Morocco, I’d at least been able to make some sense of the written language—but Kurdish, which I’d come to study, was completely impenetrable. I couldn’t understand a word of it, and I didn’t share a second common language with most Kurdish speakers. The official ban on spoken Kurdish had recently been lifted as part of Turkey’s efforts to join the EU, but it was clear that the truce between the government of Turkey and its Kurdish citizens was an uneasy one; I wasn’t even allowed to take pictures when I was invited to the set of the one Kurdish-language TV show in the country. I left Turkey a few weeks before I had planned to, feeling that I’d set myself a challenge there that was just too difficult to overcome.

Turkey

I felt both elated and exhausted as my year wound down in Malaysia. It had been a year that had tested both my academic abilities and my emotional toughness, and I was proud of myself for getting through it, but in the last weeks it was hard not to worry about what life would be like when I returned home. My questions about how minority languages could survive a globalizing world, for the most part, had only led me to more questions. But my thirst for further travel and greater understanding had only grown. The Watson is not a research project—or if it is, it’s the beginning of one, not the end.

Malaysia

Where they are today

Political Advisor - US Mission to the United Nations

Our Programs

Our Fellows

Through two, one-of-a-kind programs we encourage students to create personal pathways, then support their journeys.